Forum

Mothers Are Teaching Their Daughters Bad Lessons About Beauty

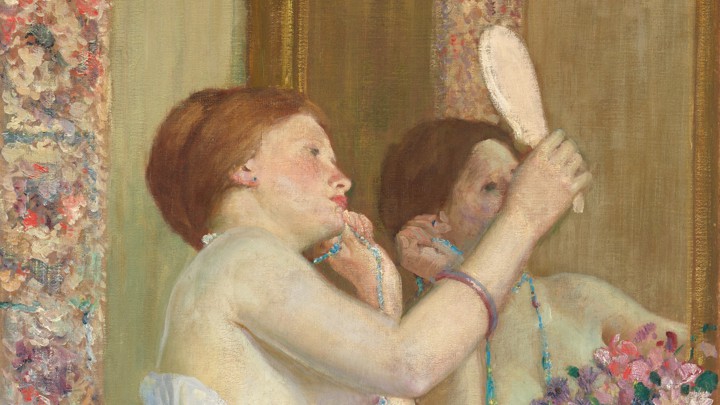

Mom guilt, that trendiest of emotions, is generally not my thing. But there is one notable exception: when I catch myself looking at myself disapprovingly in the mirror, showcasing my insecurities about some real or perceived flaw in my appearance while my 18-month-old daughter stands by as my audience of one. I feel shame because she is watching all my cultural, social, and familial conditioning about female appearance play out in front of her. It’s an internal monologue I am not eager to pass down.

As it turns out, my mom guilt may be warranted. Kids are sponges, according to an old truism. They are also monkeys, closely copying what others do. Even as mothers take pains to point out good role models for girls—for instance, those pioneering women on the soccer field or in the presidential race—we’re also transmitting to our daughters, sometimes unconsciously, our own destructive fixation on beauty. We should be doing the opposite. Indeed, deflecting attention from how girls look is one of the most important, if fraught, issues of our time.

A 2016 study in the Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology called “Body Dissatisfaction and Its Correlates in 5- to 7-Year-Old Girls: A Social Learning Experiment,” revealed what I feared: When mothers and their young daughters are put together in front of a mirror, girls emulate how their mothers talk about their own bodies. In the experiment, the mothers had to describe their body from top to bottom. One group had to say only negative things and the other group only positive things. Marisol Perez, one of the lead researchers of the study and a body-image expert, says some of the women couldn’t find anything redeeming to say about themselves. And what mothers said made a strong impression on their daughters.

“There was not a single child who did not change their response after hearing their mother say something, either in the positive or negative direction,” Perez,an associate professor of psychology at Arizona State University, told me. “The mother who said she liked her hair, the child echoed. The mother who said she didn’t like something, ditto.”

For mothers with their own appearance and body issues, having a daughter can be a difficult reckoning. The internal soundtrack of I’m fat or I need to lose weightis hard to defy. But the stakes are high for the next generation if we don’t set a good example. For a yet-to-be-published study, Perez collected data on 72 female executives to document how women’s insecurities about their looks play out in professional settings and affect their self-esteem well into adulthood. Almost half of these managerial-level women reported discomfort in socializing, and in representing their company, because they were self-conscious about how other people perceived their appearance. “We have women who have already made it to the C-suite still struggling with this issue,” Perez said.

So what’s the answer? Perez, a board member of the Academy for Eating Disorders, says she gets less traction with mothers when she talks about making changes for the sake of their own mental health and well-being than when she talks about the need to set a positive example for future generations.

But making girls feel good about themselves is a delicate matter. The internet remains fiercely divided on an age-old question: Should you tell your daughter she’s beautiful? Experts say that a constant loop of “You’re beautiful” is counterproductive. It doesn’t protect against societal messaging that conveys that girls are valued, first and foremost, for being pretty.

Moreover, there’s an element of faux empowerment in the “everyone is beautiful” movement. While the goal of wanting to broaden our beauty standards is noble, beauty is defined in part by its rarity, and it’s not everyone’s job to be beautiful, says Renee Engeln, a psychology professor at Northwestern who studies body image and the media. “If what you really mean when you call your daughter beautiful is that she is strong, smart, resilient, or funny, use those more specific adjectives instead,” she says.

What mothers do in front of their daughters likely matters even more than what they say. “I was anorexic when I was teenager, so I had some come-to-Jesus moments when I had a daughter,” says Peggy Orenstein, the author of Don’t Call Me Princess. “It was scary for me. I had to learn that it was important for my daughter to see me eat ice cream and not just have a ‘bite’ of someone else’s. I wanted my daughter to be less preoccupied with weight and food, but I needed to transcend some of my own food issues.” In practice, Orenstein says, this has meant not having scales in the house; not describing food in terms of good versus bad or fattening versus not fattening; and talking more about how foods taste and whether they leave you feeling full or not full.

At its best, motherhood can be an opportunity to question what your own family taught you about your body and to make conscious choices about which of those values—if any—you want to pass along. At its worst, motherhood can be an Instagram rabbit hole of body shame, or an endless stream of “Looking good, Mama” comments that, however well intentioned, use a person’s looks as the measure of her intrinsic worth. The result? Perez says she’s heard a 5-year-old declare, “Mommy says to sit up straight because it makes my stomach look flat.”

There are many other ways in which we unwittingly invite girls to criticize their own appearance and pursue unrealistic standards of beauty. Parents who prioritize their kids’ healthy eating but talk obsessively about cutting carbs, feeling fat, and preparing for their next juice cleanse should consider what scientific data reveal. Looking at a decade of research, Engeln says the evidence is unequivocal that talk focusing on weight, even with an eye toward “health,” is not helpful. The best practice is to portray food as fuel and to value the human body not for how it’s shaped but for what it can do. Engeln also suggests that parents, in talking with teenagers in the depths of turmoil over their body image, try to help them channel their anger and angst into answering questions such as: Who benefits when girls and women feel bad about their bodies? Who makes money off of women’s insecurities?

As a mother living in America, I’m always surprised by how often people tell my daughter, “You’re beautiful.” I don’t think her experience is unique. These comments are just part of the cultural script of what people say to young girls. I have typically responded by saying something like: “But she’s smart, too.” This gets to be tedious for me, and to others it might sound like the lady doth protest too much.

Instead, here are a few things I’ll be working on: I’m going to spend less time fretting in front of the mirror. In my household, we’re banning comments about the appearance of other women, particularly the ones running for president. Finally, I’m going to steal the stock response that Perez uses when someone tells her one of her daughters is beautiful: “And it’s the least interesting thing about her.”

We want to hear what you think about this article. Submit a letter to the editor or write to letters@theatlantic.com.

Mental illnesses like anorexia are serious and dangerous, they should be diagnosed by a doctor are often accompanies by other illnesses like depression. An over reliance on appearance is also often a problem of low self esteem. A healthy relationship between parents and children is the best protection against mental health issues in children.

I think this psychology about beauty is starting to have an impact on young males as well. Just as women are bombarded with images of the perfect woman, young boys are also seeing this in movies and on television. The only difference I see is that young boys are not usually listening to their dads complain about their pot bellies or receding hairlines. I do think young people should be encouraged to eat well, and look their best and take pride in their appearance. But they should also embrace who they are and have a healthy self image and realize that moviestars and atheletes are not the best examples of the typical human being.

Growing up my mom gained some weight and was embarrassed to go to many events that she previously had loved attending because she was self conscious of her figure. I did not think I was paying attention at the time but now when I look back I really did. She missed many fun events.

I gained weight at the time of 6th grade and was teased until 9th grade. I now catch myself slipping into the not wanting to go out because of a few extra pounds I've added. I think back to my mom right away. She did not realize this issue until years later. She told me not to stop doing things because of body shame.

Growing up with a mother who was constantly crash dieting instead of making long term, well-rounded, healthy decisions and lifestyles choices definitely effected my body image and relationship with food. A girl growing up with a mother who would focus intently on her beauty I imagine would have a similar effect on how they view beauty and how they view esthetics. I do think it's interesting though, the author's opinion about saying a daugheter's beauty is "the least interesting thing about her". On the surface I can understand the effort towards not focusing solely on women's looks. But, if my mom had said this about me growing up, it would have hugely turned me away from the joy I get from makeup and creating "pretty" looks. A women's beauty maybe something that makes her genuinely happy.

I never grew up with much of of a weight problem, the biggest I've been is almost 130 pounds. But, I was bullied in mostly 5th grade about how hairy I was. It was painful because I couldn't change it. Even my mom was embarrassed by how long my hair was getting like my armpit hair that everyone could see. She made me get my eyebrows and lip waxed when I was 10 and I also started shaving my legs then too. I don't think that looks should be the main focus of a person, but I do think people should take care of themselves. I like to do my hair and makeup to look nice and feel more confident and personally I don't think there's anything wrong with that. I deleted my Instagram, which is a huge social media platform, about 5 months ago and I believe it has helped with my depression and anxiety and with my confidence because I'm not constantly looking at all these other girls and feeling bad about my body or the bumps or acne on my face. Social media makes it so you not just worried about people you know seeing you when you go out, it makes you worried about all these strangers who will judge you.

Sometimes inadvertently comment or talk about the so called beautiful body image we see in the media. Our daughters, grandchildren etc. hear this and some develop a discomfort and lack of self esteem regarding their own body image. This can effect all areas of life. Some girls as young as 10 years old already have dieted and there are disorder clinics to help deal with these issues.